“We do not regard 3-D as a passing fancy, nor do we believe that its interest relies on a so called ‘gimmick’ value.”

Hal Wallis: March 11, 1953

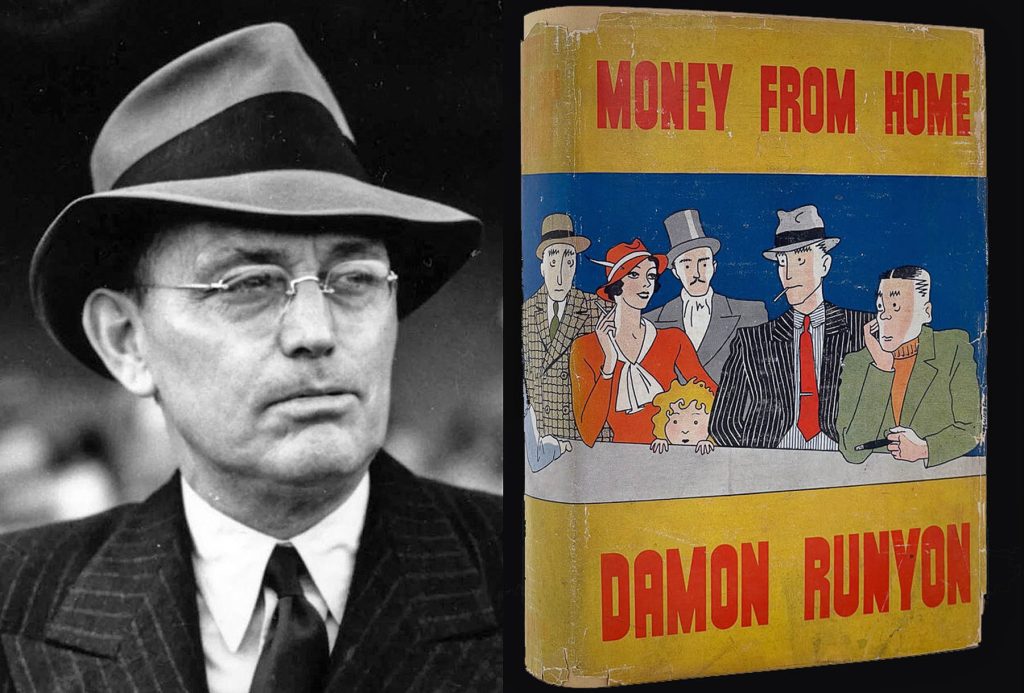

The origin of MONEY FROM HOME begins two decades before the actual production. The success of LITTLE MISS MARKER, based on a short story by Damon Runyon, prompted Paramount to purchase the rights to Runyon’s upcoming book, Money from Home, on August 1, 1934, two months after MARKER’s release and three months prior to the book’s publication. That same month, the studio announced their intention to adapt the racetrack story as a vehicle for one of their leading stars, Bing Crosby. However, these plans were dropped when it was determined Crosby already had too many assignments on his schedule.

On September 14, 1935, the Los Angeles Citizen News reported that Paramount was now preparing a Money from Home adaptation with Jack Oakie in the lead role. Despite glowing praise for Runyon’s book by journalist (and future film producer) Mark Hellinger, the project was shelved and the property sat dormant until 1952.

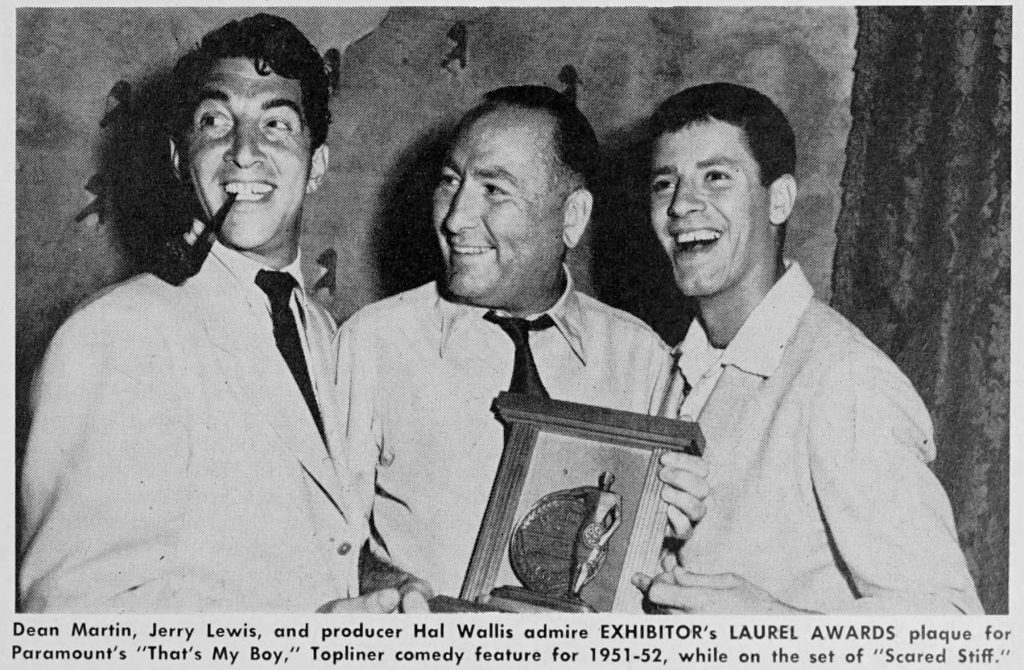

By the early 1950s, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis were not only Paramount’s biggest stars, they completely dominated the entertainment industry, with successful shows on television (The Colgate Comedy Hour) and radio (The Martin and Lewis Show), sold-out stage and nightclub appearances, and ranking among the Top Ten Box-Office Champions from 1951 to 1956. (They were ranked Number One in 1952.) Despite these career triumphs, Dean and Jerry had become dissatisfied with the quality of film scripts they were assigned, complaining that producer Hal B. Wallis seemed content to recycle old properties rather than devising material better suited to their talents. For example, the Wallis-produced SCARED STIFF (1953), a remake of Bob Hope’s THE GHOST BREAKERS (1940), was retrofitted for Dean and Jerry with much of the original dialogue intact. The team found this treatment disrespectful, given their stature and proven profitability.

THE CADDY (1953), co-produced by the team’s company York Pictures Corporation, demonstrated the type of movies they wanted to make, utilizing an original screenplay that provided both of their characters with backstories and individual moments in the spotlight.

In June 1952, months prior to the filming of THE CADDY, Hal Wallis acquired the rights to Money from Home (for $30,415) for his next Martin and Lewis picture. Damon Runyon’s book, a collection of short stories, had languished at the studio for 17 years and Wallis evidently felt the main story, Money from Home, would serve as a good showcase for the team. Yet the material was problematic. Runyon’s coarse, colorful, slang-riddled writing style didn’t always lend itself to a direct translation to the screen, and the racial elements aged badly. Additionally, Runyon wasn’t strong on narrative in regard to motivation and logic. As a result, his characters wander from one predicament to another, without a satisfying cumulative effect. At least not in the case of Money from Home. (Admittedly, it’s not considered to be among his most noteworthy efforts.)

James B. Allardice and Hal Kanter were tasked with turning the short story into a suitable screenplay. AT WAR WITH THE ARMY, Dean and Jerry’s first starring vehicle, was based on Allardice’s same-titled play. Allardice had also written material for SAILOR BEWARE and JUMPING JACKS. Kanter would later work on the screenplay for ARTISTS AND MODELS.

As Kanter told film historian Michael Schlesinger in 2003, “[Jimmy] and I did the adaptation before we decided it was going to be a Martin and Lewis picture. First we just adapted the Damon Runyon story. Then when we got the green light that it was going to be for Dean and Jerry, I was given free reign. The only really Runyonesque thing about the show, other than the basic storyline, such as it is, was the narration at the beginning, which was all done in Runyonesque first-person singular [the author’s trademark style].”

The changes made by both writers improved the unwieldy source material. In the original story, the lead character is Eddie Yokum, an aspiring (and untalented) vocalist who is mistaken for the Honorable Bertie Searles, a British jockey, thrusting him into the Runyonesque world of gamblers, gangsters, bookies and the horse-racing set. Eddie isn’t a particularly endearing character to begin with, and his dislike of animals–especially horses–renders him even less sympathetic. For the screenplay, the character’s name was changed to Virgil Yokum (played by Jerry), a simple modification that tags him immediately as a naif. Another key change was to make Yokum an animal lover and aspiring veterinarian. With the film’s horse-racing backdrop, it’s a better fit for the character and the plot.

In the original story, there’s no equivalent to Dean’s Herman “Honey Talk” Nelson character (Virgil’s cousin), a smooth-talking racetrack tout who has more success with the ladies than he does at picking winning horses. In creating Honey Talk, Allardice and Kanter showed a keen awareness of the Runyonesque style and use of descriptive monikers, while providing Dean with a role well-suited to his roguish charm and humor.

Runyon’s story ran a brief sixty-five pages, with the characters and events becoming bottlenecked during a hectic steeplechase finale, as Eddie Yokum, Bertie Searles and Marshall Preston (the nominal heavy of the piece) all ride their respective horses. (With the real Searles participating in the race, Yokum masquerades as a black jockey in order to ride the prize horse owned by his newfound love interest, Phyllis Richie.) The film adaptation had the luxury of introducing characters and plot points at a deliberate pace, giving the proceedings a progression and logic missing from the Runyon story. The screenplay pairs Honey Talk Nelson with Phyllis Leigh (changed from Richie), while Virgil Yokum is matched up with Dr. Autumn Claypool, a female veterinarian. Bertie Searles becomes a genial gentleman jockey with a fondness for drink, and Marshall Preston remains the hissable villain. Add to the mix a Poojah, his harem, and a host of Runyonesque supporting players with names like Jumbo Schneider, the Seldom Seen Kid, Short Boy and Philly the Weeper, and it’s a compact, efficient adaptation of a short story that had to have been a challenge to expand into a feature-length film.

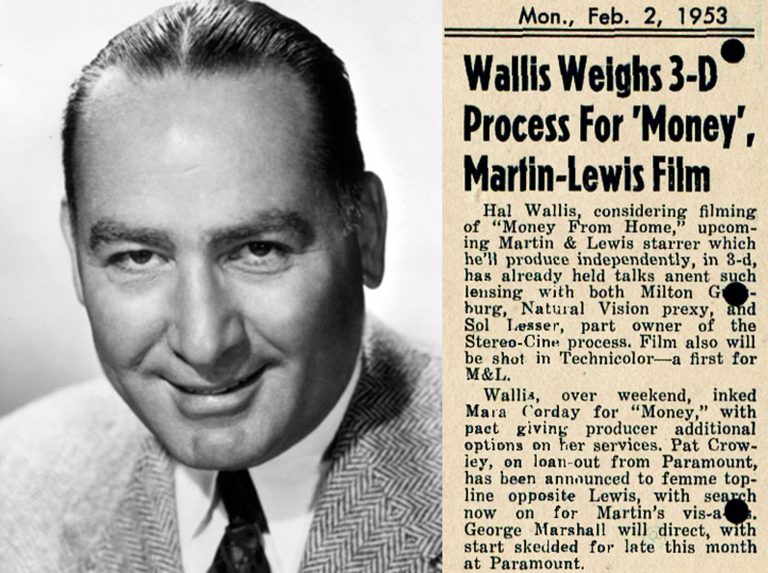

On February 2, 1953, an article in Variety noted that Hal Wallis was considering filming MONEY FROM HOME in 3-D in addition to being the first Martin and Lewis picture photographed in Technicolor. (Wallis held discussions with Milton Gunzburg, developer of the Natural Vision 3D system, and Sol Lesser, of the Stereo-Cine process.) That same day, production on THE CADDY resumed after a delay due to injuries Jerry suffered in a motor scooter accident. THE CADDY finally wrapped on February 23, 1953, as the starting date for MONEY FROM HOME was pushed back from February 9 to March 9.

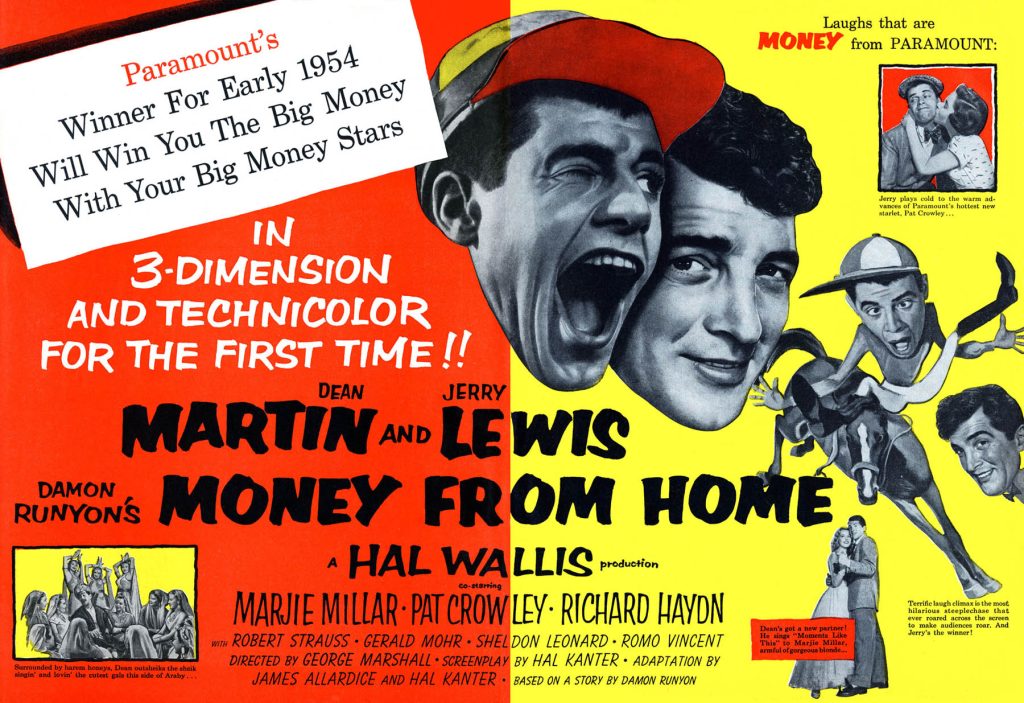

Wallis lined up the cast, with an eye on selecting actors best suited to bring the Runyonesque characters to life: Richard Haydn (Bertie Searles), Gerald Mohr (Marshall Preston), Pat Crowley (Dr. Autumn Claypool), Sheldon Leonard (Jumbo Schneider), Romo Vincent (The Poojah), Jack Kruschen (Short Boy), Phil Arnold (Fat Phil), Lou Lubin (Sam), Sam “Kid” Hogan (The Society Kid) and Frank Mitchell (Lead-Pipe Louie), among others. Wallis cast Los Angeles Times columnist Henry McLemore as a race judge, and actress/model Mara Corday was signed to play Mary the waitress. (The bulk of her footage didn’t make the final cut). Although his casting was announced in the trade journals, B.S. Pully (GUYS AND DOLLS) did not appear in the film. (He was replaced by Sheldon Leonard.)

Robert Strauss, who co-starred with the team in SAILOR BEWARE and JUMPING JACKS, was cast as the Seldom Seen Kid, one of Jumbo Schneider’s henchmen. Newcomer Marjie Millar was cast as the female lead, Phyllis Leigh. Joe Stabile, brother of the team’s bandleader Dick Stabile, was given a brief bit as a bandleader at a society party. (Years later, Joe would become Jerry’s manager.)

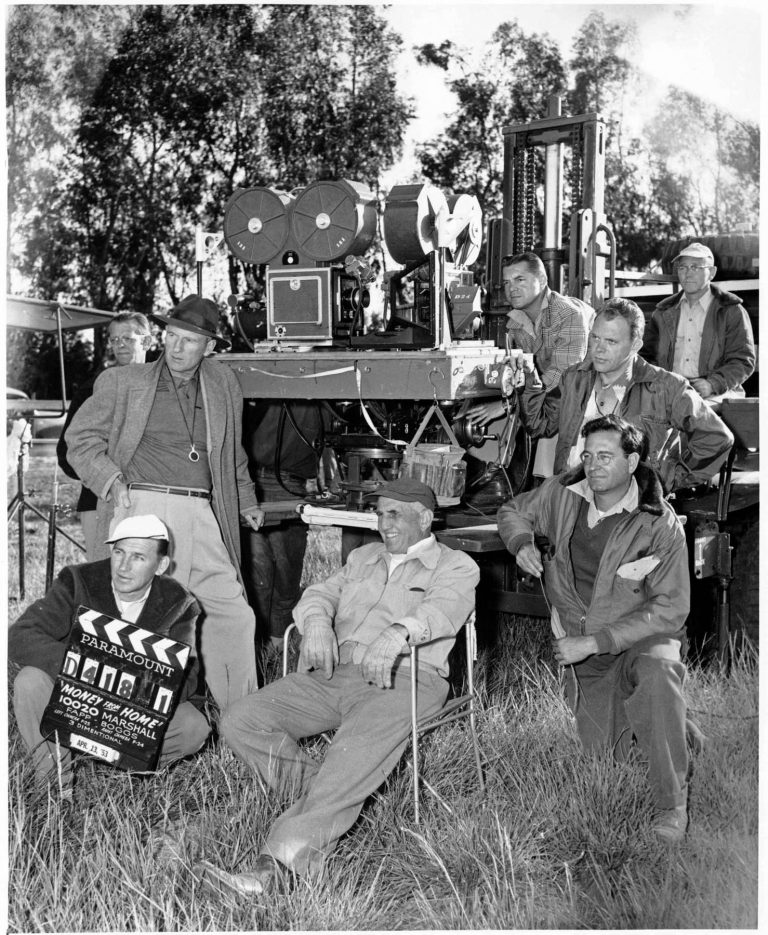

George Marshall, a seasoned veteran, was hired to direct (Marshall had directed the team in MY FRIEND IRMA, their film debut, and SCARED STIFF), while Byron Haskins (WAR OF THE WORLDS) was contracted to “direct the photographing of certain steeplechase scenes” in England.

It was an intensely busy period for Dean and Jerry. Between February 2 and May 8, they began recording episodes of their radio program, stockpiling the shows for broadcast through June. Their guests included Donna Reed, Terry Moore, George Raft, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Marilyn Monroe, Gloria Swanson, Phil Harris, Jack Webb, Mitzi Gaynor, Linda Darnell, Vic Damone, Laraine Day, Anne Baxter, Joanne Dru, Fred MacMurray, Debbie Reynolds, Jeff Chandler, Phyllis Thaxter, Vera-Ellen, Ida Lupino, Joseph Cotten, Marlene Dietrich, and Gloria Grahame.

The overload of professional commitments strained the relationship between Dean and his wife Jeannie. The couple separated on February 10 and Dean moved in with Mack Gray, a close friend and the team’s music publicist. Jeanne told a reporter for the Miami Daily News, “Dean has a great many responsibilities and is overworked. He was miserable and had to get away by himself, which he has had to do many times in his life before, and work it out alone.” About ten days later, Dean moved from Gray’s Wilshire Boulevard bachelor’s apartment to the guest room in Jerry’s home in Pacific Palisades. The comedy partners were literally closer than ever.

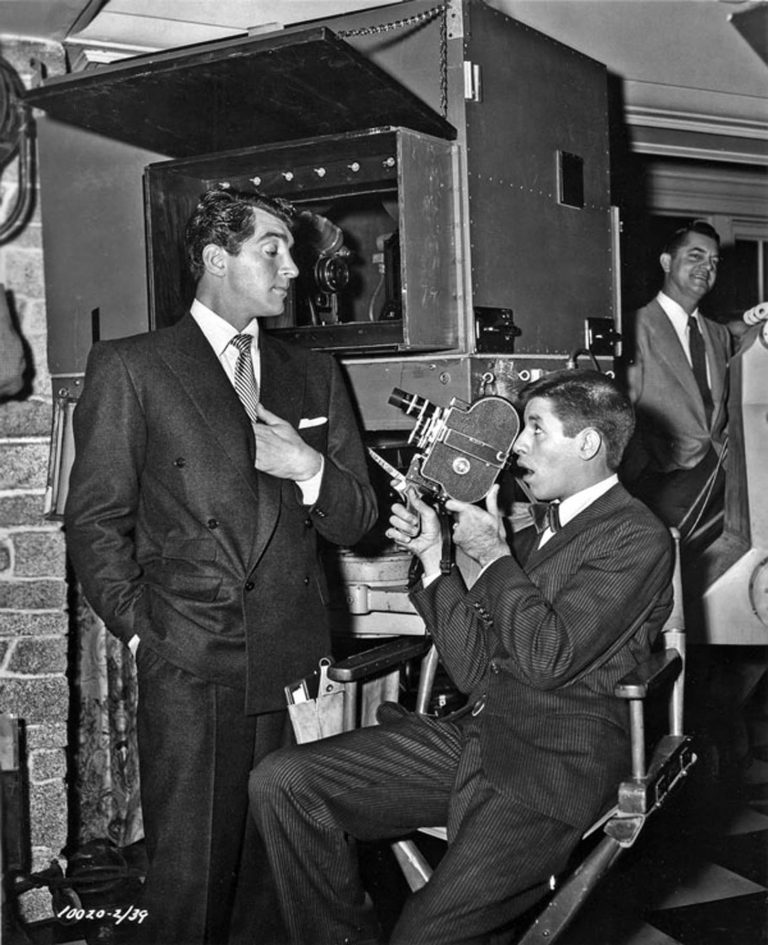

How much “alone” time Dean had during this living arrangement is open to conjecture. Not content limiting his filmmaking activities to his hours at the studio, Jerry financed a series of home movies parodying popular motion pictures of the era. (FAIRFAX AVENUE, “the Jewish SUNSET BOULEVARD; THE RE-INFORCER, a riff on Humphrey Bogart’s THE ENFORCER.) Referring to them as “home movies” is misleading because they were far more elaborate and ambitious than a hobbyist’s casual pastime. Shot in 16mm with synchronized sound, they were directed and photographed by Jerry, written by Jerry and his film/TV collaborators Harry Crane and Danny Arnold, and featuring casts of family members and friends (including Dean, Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Shelley Winters and Mona Freeman). These homegrown efforts were described as “Gar-Ron Productions,” named after Jerry’s oldest sons Gary and Ron.

During his time as a guest in the Lewis home, Dean appeared in GO AWAY, LITTLE SHIKSA, Jerry’s takeoff on COME BACK, LITTLE SHEBA. Dean, Jerry’s wife Patti, Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis took on roles played in the original film by Burt Lancaster, Shirley Booth, Terry Moore and Richard Jaeckel.

Dean told Tom E. Danson of the Daily Breeze, “[Jerry is] an amazing guy, his mind is like a trip-hammer…Everything he does is done with a purpose. For example, his home movies. There was a lot of talk about them, as you know, and people just laughed and chalked it off to a kid having fun with a hobby. But nothing could be farther from the truth…He has a tremendous capacity for detail and a memory that makes an elephant look like the absent-minded professor.”

Later, Jerry caught up with Danson to provide his response to Dean’s remarks: “Sure, I do most of the routine paperwork concerning the act but, in my book, if there wasn’t a Dean Martin there wouldn’t be any paperwork to do…Dean has as many funny lines, bits, or whatever you want to call them, as I do but since he does them in the wonderfully casual way, you just don’t realize what he’s doing. Ask any comic in the business and they’ll all tell you Dean has a wonderful sense of timing.”

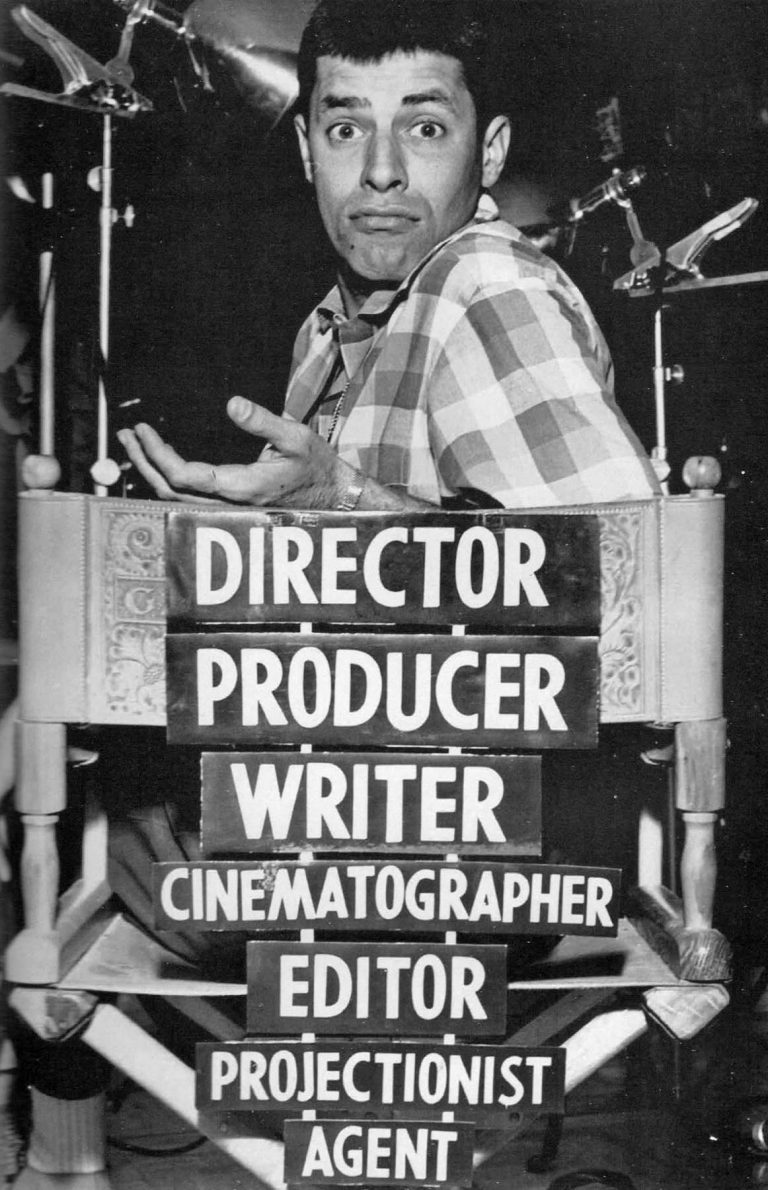

These amateur productions were an outgrowth of Jerry’s increasing obsession with the filmmaking process and a precursor to his later career as a “total filmmaker.” Jerry had co-written and co-directed scenes in Martin and Lewis movies without credit. MONEY FROM HOME marked the first and only time he received a specific onscreen credit–“Special Material in Song Numbers Staged by Jerry Lewis”–during the team’s partnership. Dean consented to this credit in an agreement dated April 23, 1953, signed by Dean, Jerry and Hal Wallis.

(Dean and his wife Jeanne reconciled in late April; Jeanne gave birth to their son Ricci on September 20.)

On the evening of February 25, Hal Wallis and George Marshall shot secret tests of Dean and Jerry in 3-D, along with flat black-and-white and flat Eastman color tests. On the afternoon of March 6, Wallis and Marshall filmed tests with the Technicolor Dynoptic camera. A memo from Paramount production manager Frank Caffey, dated the same day, concluded:

Using our present tentative budget on MONEY FROM HOME we have arrived at a combination of figures I think you will find interesting:

Shooting the picture in black-and-white 2-D – $1,251,000.

Shooting the picture in black-and-white 3-D – $1,279,000 (or an increase of $28,000).

Shooting the picture in Technicolor 2-D – $1,330,000.

Shooting the picture in Technicolor 3-D – $1,439,000 (or an increase of $119,000).

Shooting the picture in Ansco Mazda, or Eastman Mazda, in either case 3-D – $1,402,000.

In each case, the figure is based on a 36-day shooting schedule on the assumption that we will not lose any time when we shoot 3-D. We are also assuming we will not have to do any sizable amount of looping that might be caused by noise from the 3-D cameras. However, these are obviously hypothetical assumptions.

On February 28, newspapers reported that Dean and Jerry went to Palm Springs for five days of rest before launching into ten straight upcoming months of work.

After screening 3D test footage on the afternoon of March 7, Wallis signed a contract with Technicolor for use of the Technicolor Dynoptic rig.

Dean and Jerry reported to the studio earlier in the week for pre-recording dates for the songs in the film, with Dean singing the standards “I Only Have Eyes for You” (by Harry Warren and Al Dubin) and “Moments Like This” (by Frank Loesser and Burton Lane), plus two new tunes (by Jack Brooks and arranger/conductor Joseph J. Lilley), “Love is the Same” and Jerry’s “Be Careful Song.”

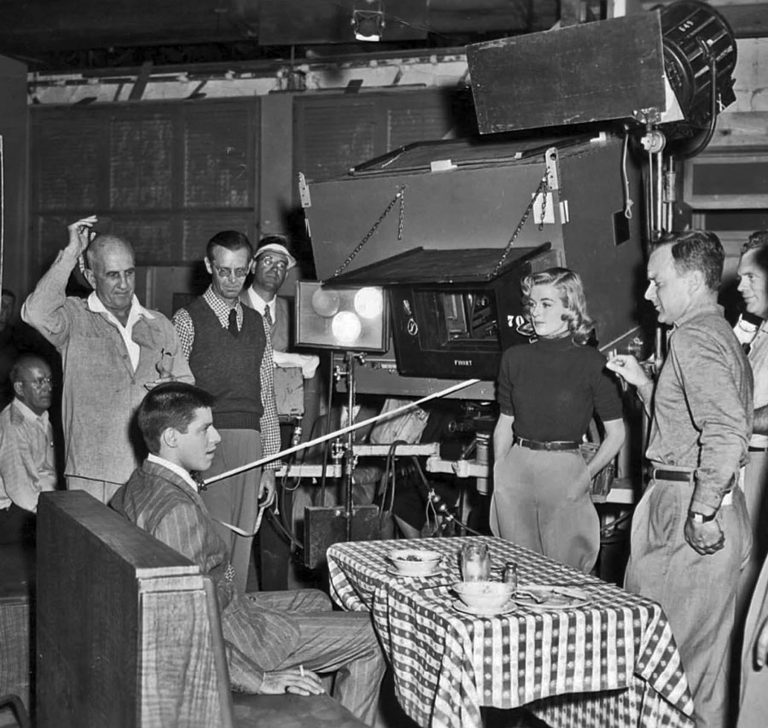

Principal filming began on March 9, 1953. Appropriately enough, Dean and Jerry indulged in their usual horseplay. Art director Henry Bumstead recalled, “I worked on six Martin and Lewis pictures, including their first, MY FRIEND IRMA, and their last, HOLLYWOOD OR BUST. It was a lot of fun working on those films. [They] were always cutting up. They would cut your tie off and then the next day you’d get three new ties from Sy Devore [a custom tailor who was a favorite among Hollywood stars]. Or they would take your wristwatch off, drop it and step on it, and then they’d bring you a better watch the next day. There was always something going on a Martin and Lewis set.”

For co-star Pat Crowley, the work environment was a far cry from her previous movie experience. “[Dean and Jerry] were so great. I had done a film before that [FOREVER FEMALE] and it was kind of serious. The people in the film were not in the best of moods. Bill Holden, Ginger Rogers, Paul Douglas. So I thought that was the way it was. Then I got to do a Martin and Lewis film and what a difference! So much fun. They were just delightful. Jokes all the time except when they got to do the work and then they were very prepared, very professional. They couldn’t have been nicer to me.”

The practical jokes weren’t limited to the comedy team, as Hal Kanter discovered:

First time I walked on the set, George Marshall turned to his script girl and in between setups he said, “Let me see the titles.” And she handed him the script. I was appalled. The titles? I immediately went to Hal Wallis’ office, stormed in and said, ‘What the hell are you doing to me? That old man still refers to the script as ‘the titles’! Where’d you get this guy?” Wallis said, “Relax. That old man knows more about putting comedy on the screen than any of the kids you can find around today.” I went back on the set later and found out that George said that just to arouse me, which he did. And I found out he did know more about putting comedy on the screen than any of these new young kids around. As a matter of fact, later on, George came to work for me in television.

There was no shortage of praise for George Marshall. Henry Bumstead: “George was a fantastic comedy director and the nicest man to work with. He was so versed in comedy. He was unbelievable and I thought he did a great job with MONEY FROM HOME. He would walk on a set and say, ‘Well, I didn’t visualize the door over there but maybe it’ll work better over there.’ That’s the kind of man he was. It was a delight working with him.” Pat Crowley: “George was great. Just an easygoing, sweet guy. He was so easy to work with and such a good director. I worked with him later on RED GARTERS.”

Hal Kanter added: “There’s a good example of George’s eye for comedy in MONEY FROM HOME. There’s a scene where Jerry goes to the door to go out and one of the heavies [Jack Kruschen] hits him in the jaw. Jerry closes the door and comes back and then he reacts and falls to the floor. That’s George Marshall. That was his idea. He really was a spectacularly funny man. George never saw dailies. I said, ‘Why don’t you come and see [them]?’ He said, ‘If I don’t know what’s on the film by now, I should hand in my card.’ He always knew what was on the film.”

One aspect of the production that Jerry Lewis remembered vividly was just how unbearably hot it was on the set due to the extra lighting required to shoot in 3-D. He told Bob Furmanek:

I remember our cameraman Danny Fapp very well. He was such an incredible talent and shot nine of our films. I learned a lot by watching him and asking questions. I watched tons of equipment being moved on the custom-built cranes and dollies. Years later, our key grip Carl Manoogian talked about that camera dolly and said the weight of it almost killed him. I was amazed at the amount of light used, and how Fapp was able to control the exposure. We were absolutely melting, and I remember Pat Crowley melting before my eyes during one take where our director George Marshall took too long to roll the cameras.

Variety (March 24, 1953): “Another new term to be added to the growing list of 3-D palaver has cropped up on the set of Hal Wallis’ MONEY FROM HOME. When the cameraman calls for the ‘pallbearers’ he gets the technicians who lift the large coffin-like casing on and off the new Technicolor 3-D camera.”

The race sequences involving the primary cast were filmed at the Devonshire Stables and Racetrack at Northridge Farms in the San Fernando Valley, transformed into a Maryland steeplechase ground. To play steeplechase jockeys, Hal Wallis signed “seven of America’s greatest horsemen”: Jerry Ambler (world’s champion bronc buster), Jack Connor (holder of 15 rodeo and horse show cups), John Eppers (rider and breeder), Chick Hannon (champion bulldozer–steer wrestling–at the Calgary Canada Rodeo), Willard Willington (record-holder for roping), Don House (blue-ribbon jumper), and Ervie Collins (winner of 22 titles in major U.S. rodeos for bulldozing and bronc busting).

Some cast members dealt with health issues and injuries. Riding a horse for the steeplechase sequence, Jerry fell into a water hole, didn’t change into dry clothing, and wound up catching a bad cold that held up production. Gerald Mohr, an expert horseman, was thrown and injured by a seven-year-old mare while teaching Jerry how to ride. Pat Crowley was stepped on by horses on three separate occasions, tripped over light cables twice, bitten on the knuckle by a monkey, banged on the head by a windblown reflector, and toppled off a rail fence. While on location at Northridge Farms, Romo Vincent fainted after standing for two hours in the sun. For his role as the Poojah, Vincent’s costume–which included a turban, amulets and chains–weighed a reported 35 pounds. He was revived by the studio doctor on the set and after a short rest was allowed to continue working.

Jerry’s 27th birthday fell on March 16 and a surprise party, arranged by Brian Seltzer, Wallis’ Director of Publicity, was thrown on the set, with Dean popping out of a prop cake. At home, Jerry’s wife Patti, who sang with the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra in the 1940s, presented him with a private recording of “My Lover, My Hero, My Own,” composed by Danny Arnold, one of the team’s writers, and their pianist Lou Brown. On the B-side of the record, Dean sang the tune with different lyrics: “You Ratface, You Bastard, You Jew.”

Motion Picture Herald (March 21, 1953): “Hal Wallis, producer of the currently shooting Dean Martin-Jerry Lewis 3-D film, MONEY FROM HOME, this week laid claim to having filmed the most spectacular shot yet made in three dimensions. It was a New York street scene encompassing an area equivalent to three city blocks, shot by a 735-pound camera mounted on a 47-foot boom and on a dolly with 600 feet of track. This, said Mr. Wallis, was proof that the 3-D filming process had graduated from the gimmick stage to top technical performance.”

During production, Dean and Jerry were quoted echoing Wallis’ pro 3-D stance, with Dean telling columnist Ben Cook, “We’ll be so close to the audience we’ll be able to swipe popcorn from them. The audiences feel they can reach out and touch the actors, just as they can in a nightclub. It means we won’t have to change our style. As a matter of fact, certain limitations we’ve had to put up with in ‘flatties’ will no longer exist. We’ll be free! Watch out, we’ll be free!”

Jerry added, “Quick cuts are out. The camera doesn’t have to jump from one person to the other to register individual emotions. Everybody is in focus no matter where they stand and their reactions are plainly seen without huge closeups. For instance, Dean could be singing a song right up in front of the cameras and I could be ruining it for him right behind his back at the same time. This is delightful!”

These upbeat comments made for positive publicity, yet a few months after production wrapped, Jerry couldn’t conceal his misgivings. He told W. Ward Marsh of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, “When we heard that they wanted us to do a 3-D picture, we were not happy. Dean and I discussed it long and seriously, and it was finally decided that I should go to Wallis and tell him we are opposed to 3-D for us at this time. In a couple of years, or when we’re no longer hot at the box offices, will be time enough for the gimmicks but he felt that now is the time, so we made it. It more than doubled the costs, but it is still the story which counts and the public will accept a good story on a little screen. We forget there are other places besides New York and Hollywood to please, and that great public in between will take the picture in any form–if you tell a GOOD story! Well, we have a 3-D [picture] but we don’t need gimmicks.”

In an interview with Kaspar Monahan of the Pittsburgh Press, Jerry noted, “I told them at Paramount, look, in us you got the No. 1 box office attraction in movies. Why do you team us up with a gimmick? We don’t need it. No good film story needs it.”

MONEY FROM HOME wrapped on May 1, 1953, after 47 days of filming, 10 days behind schedule due to various production delays. In addition to the aforementioned mishaps and injuries, there were delays attributed to “accumulated slow progress” in production records. For example, on April 3 Jerry reported to the set at 9:00 a.m. yet didn’t shoot his first scene for the day until 5:40 p.m.

With filming completed, Dean and Jerry hit the ground running. On May 3 they hosted The Colgate Comedy Hour at the El Capitan Theatre in Hollywood. MONEY FROM HOME co-stars Sheldon Leonard and Jack Kruschen also appeared on the show. On May 4 Dean recorded four songs for Capitol Records, while Jerry was in San Francisco, for a rest as per doctor’s orders. Despite this medical advice, Jerry played golf during the day with Jack Benny and Sammy Davis, Jr. at the Green Hills Country Club in Millbrae and dropped in on the Jack Benny Variety Revue (with Benny, Davis, as part of the Will Mastin Trio, and Gisele MacKenzie) that evening at the Curran Theatre. When Benny invited him on stage to take a bow, Jerry treated the audience to a full-blown nightclub performance.

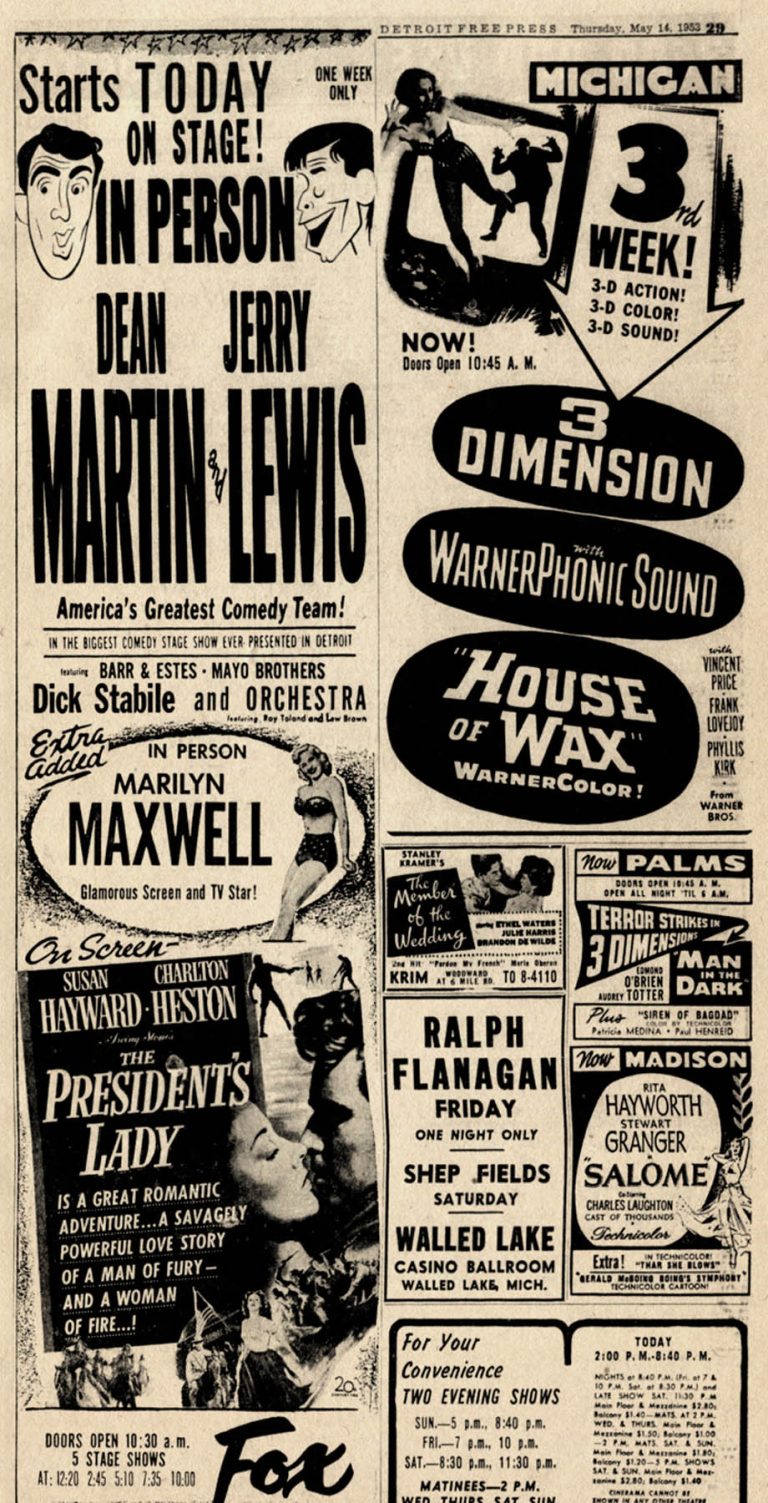

On May 7 Dean and Jerry had a lenticular 3-D photo session in Los Angeles with photographer Paul Hesse. The following day, they recorded an episode of their radio program with guest star Gloria Grahame. On May 11 they left for a personal-appearance tour, opening at the Fox Theatre in Detroit on May 14.

On May 22 they did a golf benefit with Bob Hope in Chicago. The next day they appeared with Hope at the Chicago Stadium for the Night of Stars benefit show presented by the Italian Welfare Council of Chicago. The lineup also included Tony Martin, Frankie Laine, Rocky Marciano, Tony Bennett, Jack E. Leonard, Jeri Southern and Carmelita Pope. Dean and Jerry were in Eastchester, New York on May 25 for the Damon Runyon Golf Exhibition Match at the Vernon Hills Country Club to raise funds for the Damon Runyon Cancer Fund. They were paired against Perry Como and Sid Caesar, with Denise Darcel and Dagmar serving as caddies. On May 31 they again hosted The Colgate Comedy Hour, this time at the International Theatre in New York City.

Dean and Jerry set sail for Europe on June 3, opening at the Royal Theatre in Glasgow, Scotland on June 15, then opening at the London Palladium on June 22. In July they did a six-day tour of French air force bases in Orly, Laon, Fontainebleau, Orleans and Suresnes.

MONEY FROM HOME was independently produced by Hal Wallis and his partner Joseph H. Hazen utilizing Paramount’s studio facilities. It was made without a distribution deal in place, as the producers had already fulfilled their existing contractual obligation with Paramount. Wallis-Hazen, Inc. was dissolved in June (although Hazen would continue an association with Wallis) and the film was sneak-previewed at two west coast theatres (Crest Theatre in Long Beach, Alex Theatre in Glendale) that month. It was presented with a title card reading “You are about to see a preview of a new Paramount picture,” even though no deal with Paramount had been negotiated. Nevertheless, Wallis and Hazen felt they were in a unique bargaining position as they had made the first 3-D picture with “real stars,” one that didn’t have to rely solely on the technical gimmick.

In July, Wallis began talking with Warner Brothers. Unable to reach an agreement, Warners issued a statement that they would not be distributing MONEY FROM HOME. On August 4 it was announced that a distribution deal had been made with Paramount.

Back in the States, Dean and Jerry participated in the National Celebrities Tournament at the Scioto Country Club in Columbus, Ohio on August 17, and later attended the premiere of THE CADDY at Loew’s Ohio Theatre in Columbus. Both the tournament and the premiere benefited the National Caddy Association. They headlined a two-week engagement at the New York Paramount Theatre on August 26 (six to seven shows daily), with Polly Bergen (“Dean & Jerry’s Movie Sweetheart”), Dick Stabile and his Orchestra, Barr & Estes (Leonard Barr was Dean’s uncle) and the Four Step Brothers. (The movie on screen was PLUNDER OF THE SUN.) It would mark their final stint at a theatre that held many treasured memories for Jerry. On the day they opened at the Paramount, Variety reported that the team was risking suspensions and fines from the American Guild of Variety Artists for violating union rules against “gratising”–performing for free–at assorted venues. On September 9 they hosted the Circus Saints & Sinners charity event at the Hotel Waldorf Astoria in New York City. Wonky 3-D glasses were handed out for the occasion.

After plans were dropped for their next proposed picture, the shot-on-location MARTIN AND LEWIS IN PARIS, Dean and Jerry began filming LIVING IT UP on October 19. An adaptation of the Broadway musical Hazel Flagg (February-September 1953). which was based on the screwball comedy NOTHING SACRED (1937), LIVING IT UP, photographed in Technicolor, was their first widescreen movie. Production wrapped on December 18, 1953, and the film was released on July 23, 1954.

On November 6, MONEY FROM HOME had a showing for trade-journal reviewers at the Picwood Theatre in Los Angeles. Unfortunately, the 3-D was screened out-of-sync, so while the reaction to the film itself was positive, the three-dimensional process was panned. The Hollywood Reporter: “[The] extra dimension failing to rate as an asset…The 3-D is hard on the eyes.” Variety: “The 3-D process used got a poor display at the preview, the projection being off-register often enough to cause considerable strain on the vision.”

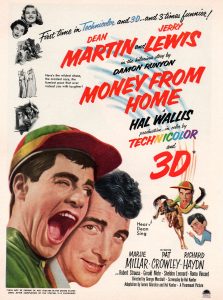

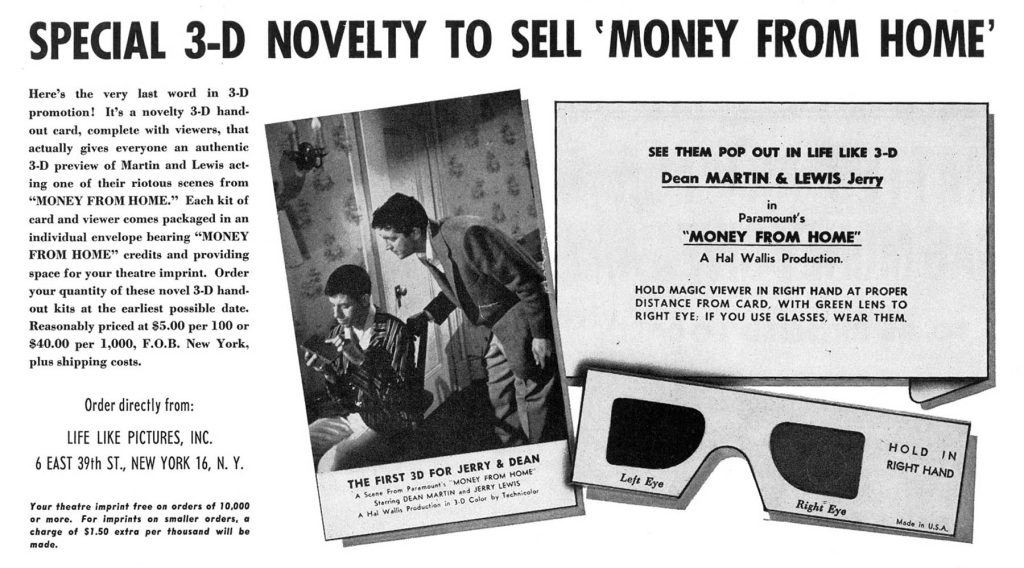

Because of the negative feedback from this faulty review, most exhibitors opted to play the film in 2-D. As a result, much of the 3-D oriented publicity material went unused, in favor of the 2-D promo items, resulting in a somewhat confusing ad campaign. The 3-D material hyped the team’s “First Time in Technicolor and 3-D…and 3 Times Funnier!” For 2-D, it was modified to “First Time in Technicolor…and 3 Times Funnier!” (Why would Technicolor make the duo three times funnier?) In the UK, it was revised to a more sensible “First time in Technicolor…and Funnier than ever before!” (MONEY FROM HOME opened in 2-D in London.)

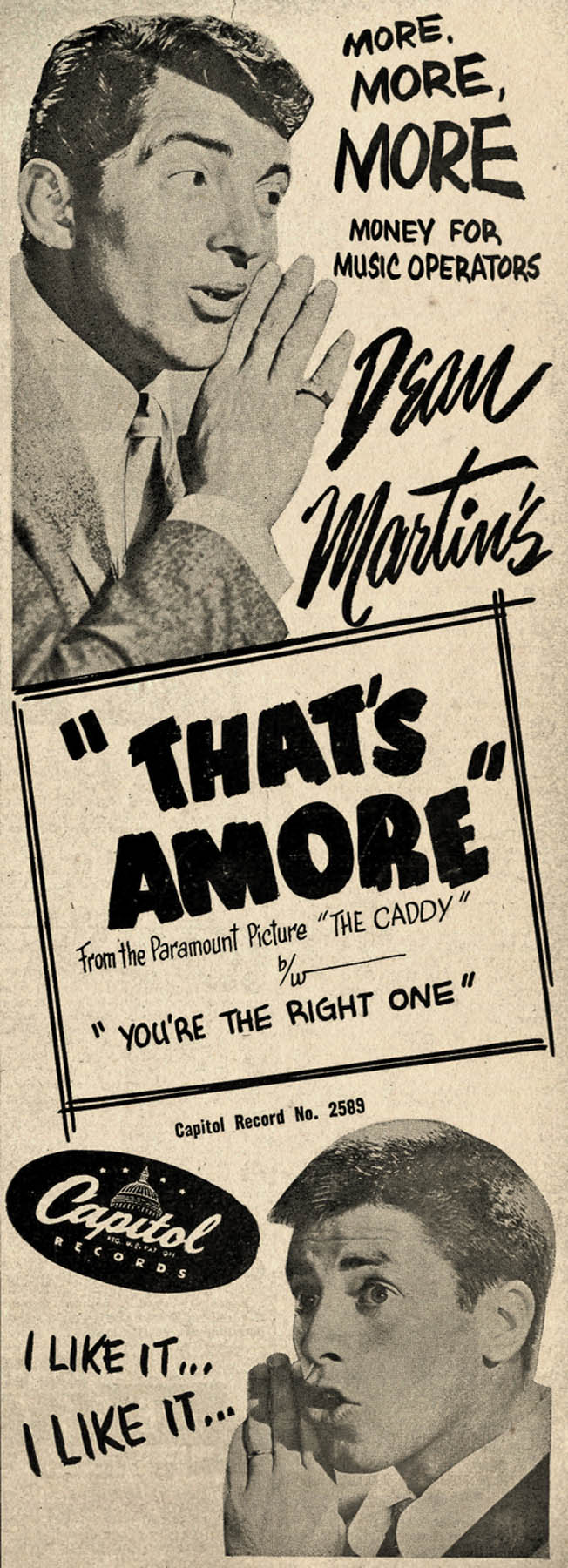

Up to this point, Dean had a respectable if undistinguished recording career at Capitol Records. Critics considered him to be a pleasant, second-tier crooner, sometimes noting that Dick Stabile’s musical arrangements were superior to Dean’s renditions. That changed with the release of THE CADDY, in which Dean sang the Harry Warren-Jack Brooks song “That’s Amore.” The recording, released November 7, was a major hit, establishing Dean as a leading vocalist and not merely just Jerry Lewis’ partner. It became one of Dean’s signature tunes and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Song (losing to “Secret Love” from CALAMITY JANE). Due to this unexpected success, the blurb “Hear Dean Sing!” was added to the MONEY FROM HOME promotional materials.

As he did with THE STOOGE, an earlier Martin and Lewis picture, Hal Wallis arranged for one-day pre-release New Year’s Eve screenings, this time at 322 theatres in key cities, including Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, San Francisco, Memphis, Milwaukee, Indianapolis and Miami. Due to a shortage of 3-D prints, all of these screenings were in 2-D.

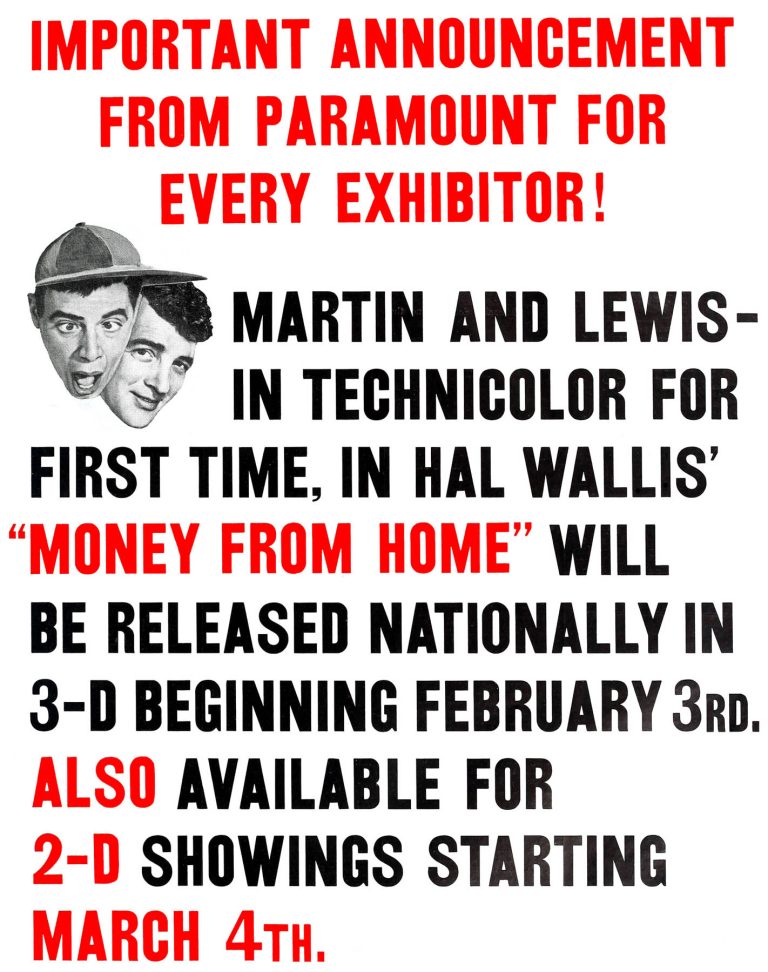

In January 1954 Paramount’s promotional department arranged with New York-based Life Like Pictures, Inc. to manufacture 3-D photos and accompanying “magic viewers” to be distributed to theaters. The following month, Paramount offered free TV promotional material (two trailers and two station-break cards) to exhibitors.

A color trade ad appearing in national magazines on January 5 stated the film “will not be shown in any theatre in the United States until after the completion of the special 3-D showings.” The national 3-D release was set for February 3, with 2-D booking available on March 4. However, on January 25 Paramount dropped the 3-D window requirement and allowed exhibitors to play the film flat. MONEY FROM HOME opened throughout the country in both formats on February 3, 1954. (It had been reported that the film would also be in stereophonic sound, like SCARED STIFF, but those plans were dropped.)

MONEY FROM HOME opened in 2-D at the New York Paramount Theatre on February 16, marking the first Paramount release to play the NY flagship theatre in over a year. (MONEY FROM HOME wasn’t screened in 3-D in New York until April 1993, when archival dual-35mm print played as part of a 3-D festival at the Film Forum.)

MONEY FROM HOME had a total of 17,576 domestic bookings and played in 3-D at only 356 theaters, resulting in only 2% of bookings intended for the 3-D version.

Reviews were mixed. Some critics felt it was another entertaining effort by the team, while others were underwhelmed:

John L. Scott, Los Angeles Times: “Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis take off like a slow freight, but finish like a jet plane in their new comedy romp. The stellar comics fit their roles well, Martin especially turning in an excellent performance as the Runyonesque character. Lewis, of course, is Lewis. What more can one say? Miss Millar impresses favorably in her initial featured role. She has beauty, poise and handles her lines well. Miss Crowley likewise scores as the cute foil for Jerry’s farcical ranks. Richard Haydn plays the screwball jockey. Robert Strauss, Romo Vincent and Gerald Mohr add to the fun.”

Dick Williams, Los Angeles Mirror: “Whoever dreamed up the idea of putting Martin and Lewis in a Damon Runyon story presumably is no longer employed at Paramount. Which is not to say that the boys’ new effort doesn’t have some good laughs. But they are strictly the wacky Martin and Lewis brand and have nothing to do with the late Bard of Broadway’s style of slangy humor…There are some good Lewis funnies. Best are Jerry dressed as a veiled dancer in a harem, another à la Cyrano de Bergerac with Jerry singing with Dean’s voice to the latter’s girl, and his take-off on a ritzy English steeplechase rider.”

Mae Tinée, Chicago Tribune: “While it is true that some of the situations and gags are anything but new, they’re presented in typical and M. and L. fashion, and brought loud hoots of laughter from the audience…Judging from the reaction from the audience and the lines of fans waiting patiently to see the film, this movie should be a money-maker of the kind that will put the boys in a higher tax bracket.”

Otis L. Guernsey, New York Herald Tribune: “Even avid fans of the Martin-Lewis ginger ale comedy may find MONEY FROM HOME a bit flat, as though the stuff had been watered to get a few more ounces out of the same old bottle…there is a limit to what the comic can do with pure absurdity, and it looks as though the Messrs. Martin and Lewis have come pretty close to it.”

Mildred Martin, Philadelphia Inquirer: “[The] adapters and Director George Marshall have had some difficulty combining the stars’ individual brand of hijinks with pre-Prohibition Runyon antics but a compromise has been affected which leaves the boys in their customary uninhibited form. And while it’s a case of now you see it, now you don’t, so far as Runyon flavor goes, Dean and Jerry carry on at the old familiar stand, dispensing gags, slapstick, double takes, songs and grimaces to their hearts’ content.”

Opposing opinions notwithstanding, MONEY FROM HOME would eventually bring in $2,800,000 at the box office (the average ticket price for a movie in 1954 was 49 cents), making it the 22nd highest-grossing film of the year.

A Deeper Look by Mike Ballew

It cannot be overstated: The phenomenal success of Arch Oboler’s 3-D jungle adventure Bwana Devil starting in late November 1952 turned Hollywood practically on its head. The moviegoing public clearly wanted 3-D and was willing to wade through a widely panned film to get it. Within weeks, most major studios and a host of independent producers leapt headfirst into 3-D production.

Producing partners Hal Wallis and Joseph Hazen were very bullish on the prospects of 3-D, not just from a business angle but as an exciting new addition to the motion picture art. Wallis wanted to put his top box-office stars, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, into a 3-D film as soon as possible, so he and Hazen began investigating 3-D filming systems in January 1953 for their upcoming production, Money from Home.

Their first choice was Milton Gunzburg’s Natural Vision. First used to film Bwana Devil, Natural Vision was also being used for a brand-new picture just starting production at Warner Bros., House of Wax. Wallis and Hazen also took a serious look at the highly portable Stereo-Cine system financed by longtime Tarzan producer Sol Lesser. On the strong recommendation of the Polaroid Corporation, the partners also considered two uniquely designed camera rigs built from the ground up by the Producers Service Company of Burbank. But Wallis and Hazen soon learned that every available camera rig of all three varieties was already tied up with other productions, some underway, others soon to begin shooting. What’s more, the purveyors of every 3-D system in town demanded (and were usually getting) lavish terms for the use of their equipment and expertise. Natural Vision, for instance, was guaranteed a $25,000 advance against a 5% cut of a given picture’s total gross receipts—whether or not it was ever actually shown in 3-D.

Wallis and Hazen decided to consider another option closer at hand. While Money from Home would be an independent production, the film would be made on the Paramount lot using Paramount production facilities. And Paramount had a perfectly serviceable stereoscopic camera rig of its own, Paravision, then being used to shoot the antebellum costume romance Sangaree. Footage from Sangaree looked great in the dailies, so Wallis and Hazen commissioned a brand-new Paravision rig for use on Money from Home at a total cost of $5,267.83. This new unit would not be ready in time for their projected start date, but an availability window of several weeks after the close of Sangaree would allow the original Paravision rig to serve as a temporary stopgap.

The total absence of a daily production report for Sangaree on February 25, just three days before that film’s close of production, may indicate that the 3-D tests of Martin and Lewis known to have been filmed that day were made using the lone available Paravision rig, possibly on Sangaree sets. We can reasonably surmise that Stereo-Cine was likely also tested that day.

But other troubles still threatened. For one thing, the “borrowed” Paravision rig would very soon be needed for another film, the 3-D musical Those Redheads from Seattle, scheduled to begin production just one week after the start of Money from Home. Any delay in fabricating the new Paravision rig would result in a costly shutdown for one film or the other. For another thing, the inherent design of the Paravision rigs—two Mitchell NC cameras in a face-to-face configuration, peering into paired mirrors—meant that using wide-angle lenses would cause severe spatial distortions in 3-D. This would impose onerous limitations on comedic staging for director George Marshall and cinematographer Daniel Fapp. As if all this weren’t enough, the surge in production across Hollywood in the early months of 1953 suddenly put Eastman Color stock in short supply, so even if Wallis and Hazen resolved their camera dilemmas, a question mark still hung over the unbroken availability of color.

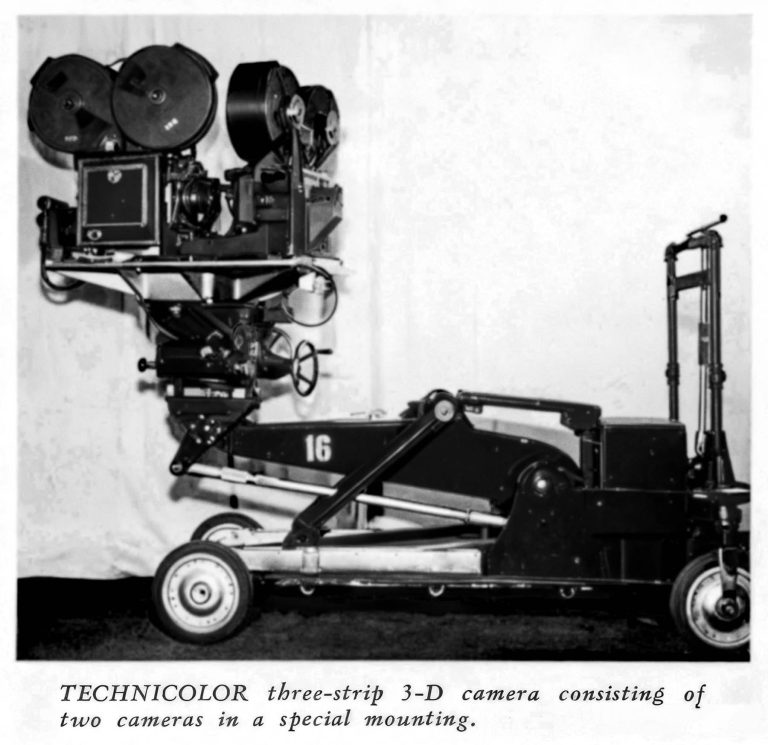

A white horse came riding to the rescue from an unexpected source: Technicolor. As late as February 6, Paramount production manager Frank Caffey reported to Jack Saper of Hal Wallis Productions that Technicolor was working out its own stereoscopic camera setup but had not progressed far enough to discuss it meaningfully. But just four weeks later, on the afternoon of Friday, March 6, test footage was made using Technicolor’s all-new, entirely proprietary Dynoptic 3-D camera rig. The footage was processed overnight and shown to Wallis and Hazen the evening of Saturday, March 7. They were reportedly very impressed—and no doubt greatly relieved.

And so, on Monday, March 9, 1953, production of Money from Home began, with three different 3-D camera rigs present on the set. Two of unknown make—quite likely Paravision and Stereo-Cine—were quietly set aside that very day. Production reports for Money from Home make clear that, starting on Day Two, only one camera rig was used for most filming—the Technicolor Dynoptic camera rig.

As a line item in the film’s budget, the Dynoptic rig cost only a fraction of what its 3-D competitors were asking. The rental of two matched Model D three-strip Technicolor cameras totaled $10,360, of which a flat $1,000 was applied to the underlying support platform. Technicolor, happy to fill lucrative orders for separate left- and right-eye release prints, demanded not one dime of the film’s gross receipts.

As you might expect, the Dynoptic rig was one heavy behemoth. Weighing in at 735 pounds, it put two of Technicolor’s signature Model D cameras in a horizontal “L” configuration on a common base. Six strips of black-and-white film ran through the rig for every single take, capturing red, green, and blue records for the left and right stereopairs. The right-eye camera “peered out” from behind a semi-silvered mirror, capturing its light through what amounted to a transparent pane, while the left-eye camera captured its light as a reflection off the front surface of the glass. (The real tech boffins among you will note that the left-eye camera actually “looked across” the optical axis of the right-eye camera.) The fact that the glass transmitted 40% of the light, reflected another 40%, and completely absorbed the remaining 20% meant that Daniel Fapp and his crew had to bathe the set in bright, hot light just to get the needed exposures.

When the left-eye camera was in its rearmost position, the lens separation (or interaxial) was effectively zero, resulting in two identical 2-D films—had that been desired. In its far-forward position, the interaxial was 4 inches, perfect for distant shots with telephoto lenses and for exaggerated depth effects with normal lenses. The bulk of filming was done with the lenses at (or just under) 2.5 inches of separation, corresponding with the average distance between adult human eyes.

The right-eye camera pivoted up to five degrees to converge on whatever subject was meant to appear in the plane of the screen. A full array of lens pairs provided focal lengths from 35 to 140 millimeters, covering every situation cinematographer Daniel Fapp might face. According to Hal Wallis, this Dynoptic 3-D rig was “far ahead of all other 3-D systems now available and has greater vitality and faithfulness to natural tones than the Technicolor 2-D process.”

Technicolor’s designated stereographer for Money from Home was Henry Imus, who handled all technical responsibilities concerning 3-D. Imus would serve the same function on a later production also shot using the Dynoptic rig, Flight to Tangier, likewise released through Paramount. Imus was somewhat conservative in his technical and aesthetic choices, giving both films robust stereo volume and pleasant depth range without subjecting audiences to eye-straining visual workouts. Camera reports for Money from Home are unfortunately incomplete, but surviving records for Flight to Tangier confirm that Imus used varying interaxials to accommodate every possible combination of focal length and camera-subject distance, deftly balancing accurate stereoscopic scale with overall viewing comfort.

In light of all this evident care, it is baffling that an early preview of Money from Home at the Picwood Theatre in November 1953 prompted sharp brickbats from the industry press. Without offering constructive details, The Hollywood Reporter claimed that the 3-D on view was “hard on the eyes,” while Variety said “the projection [was] off-register often enough to cause considerable strain on the vision.” Of course, critics and audience members who are not experts in stereo photography are not always able to communicate precisely what they dislike about troubling 3-D imagery, then or now. In this case, we can only guess whether there was a registration problem in the prints, image misalignment or illumination mismatch in the projectors, or a catastrophic loss of synchronism in the left- and right-eye images on the screen.

As it happened, a lot was riding on the 3-D success of Money from Home. Along with a handful of other prominent titles, including Kiss Me Kate, Hondo, and Miss Sadie Thompson, Money from Home was seen as a bellwether to determine the ultimate fate of 3-D in Hollywood. If these films drew healthy crowds not only because of their big stars and lavish production values but also by the attractive power of their 3-D imagery, there might be hope for 3-D as a continuing production medium in the long run.

When Money from Home opened wide in 322 theatres in select previews on New Year’s Eve 1953, every single one of those engagements was in 2-D. In all likelihood, at least some of these involved separated 3-D prints, with left-eye reels going out to some theatres and right-eye reels going out to others. Be that as it may, not many 3-D prints would ultimately be needed for Money from Home. While the film would finally pull in rentals of $2.8 million on the strength of some 17,220 2-D bookings, only $358,000 trickled in from its scant 356 3-D playdates. While there was still one more unequivocal hit to come on the 3-D horizon—Universal’s monster classic Creature from the Black Lagoon—the writing was on the wall for the third dimension in Hollywood… at least for the time being.

“That’s Amore” – Dean Martin’s “Signature Song” by John Chintala

A “Signature Song” – it’s what every entertainer dreams of recording – a tune that immediately identifies them in the public’s mind. Whether it was sung by the person themselves (“Thanks for the Memory” by Bob Hope) or used as their theme music (Jack Benny’s “Love in Bloom”) it’s a song that defines their career.

By mid-1953, Capitol Records had released almost forty Dean Martin singles since they signed him five years earlier. His biggest hit had been “I’ll Always Love You” from the Martin & Lewis flick My Friend Irma Goes West which peaked at #11 on the Billboard charts. But he had to “share” his other top twenty hits with fellow artists whose versions outranked his: “Powder Your Face with Sunshine” (Evelyn Knight) “If” (Perry Como) and “You Belong to Me” (Jo Stafford).

So, when Dean walked into the Capitol Records recording studio on Thursday night, August 13th, he most likely viewed it as just another session. The first song recorded that evening was “I Want You,” but according to the session log, only the instrumental track was laid down. The next tune would prove to be the turning point in his recording career.

Dean had already waxed “That’s Amore” the previous November on a Paramount Studios soundstage for the Martin & Lewis flick The Caddy. It was the first of the duo’s films for their own company, York Productions, and Jerry revealed in his 2005 book Dean & Me – A Love Story that he personally paid Oscar winner Harry Warren and his lyricist Jack Brooks $30,000 to write songs for the movie in search of a hit; the songwriting pair knocked this one out of the park.

Backed by Neapolitan-style instrumentation and a vocal choir which included Lawrence Welk’s future Champagne Lady, Norma Zimmer, the jovial, whimsical tune in ¾ waltz time was completed in only six takes. Dean had previously recorded such novelty tunes as “Zing -A-Zing-A-Boom,” “Choo ‘N Gum” and “The Sailor’s Polka,” so it’s understandable why he wasn’t overly enthused about “That’s Amore.” In a 1981 interview, he admitted his initial feeling was, “How can anybody buy anything with ‘moon hits your eye with (sic) a big pizza pie.’ I said, ‘that’s horrible; it’s terrible.’ And it just clicked.”

Released on September 14th, Billboard rated it a “74” in their October 3rd review noting it was a “cute ballad…sung affectionately” and that it “could attract sales loot.” Cashbox was more enthusiastic giving it a B+ and calling it “one of his best jobs to date.”

Dean performed it the following evening on TV’s Colgate Comedy Hour with a new up-tempo arrangement in the tune’s second half courtesy of Martin & Lewis’ bandleader Dick Stabile. Billboard took out a full-page ad for the single in their Halloween issue and New Orleans radio station WTIX was the first to list it in the Top Ten. Paramount Pictures even added the tag line “Hear Dean Sing” to their ad campaign images for the duo’s film Money from Home as a further enticement to movie goers. Dean would record a song from that flick, “Moments Like This,” on December 23rd while “That’s Amore” was soaring up the charts, but it remained in the vaults until the late 1990s.

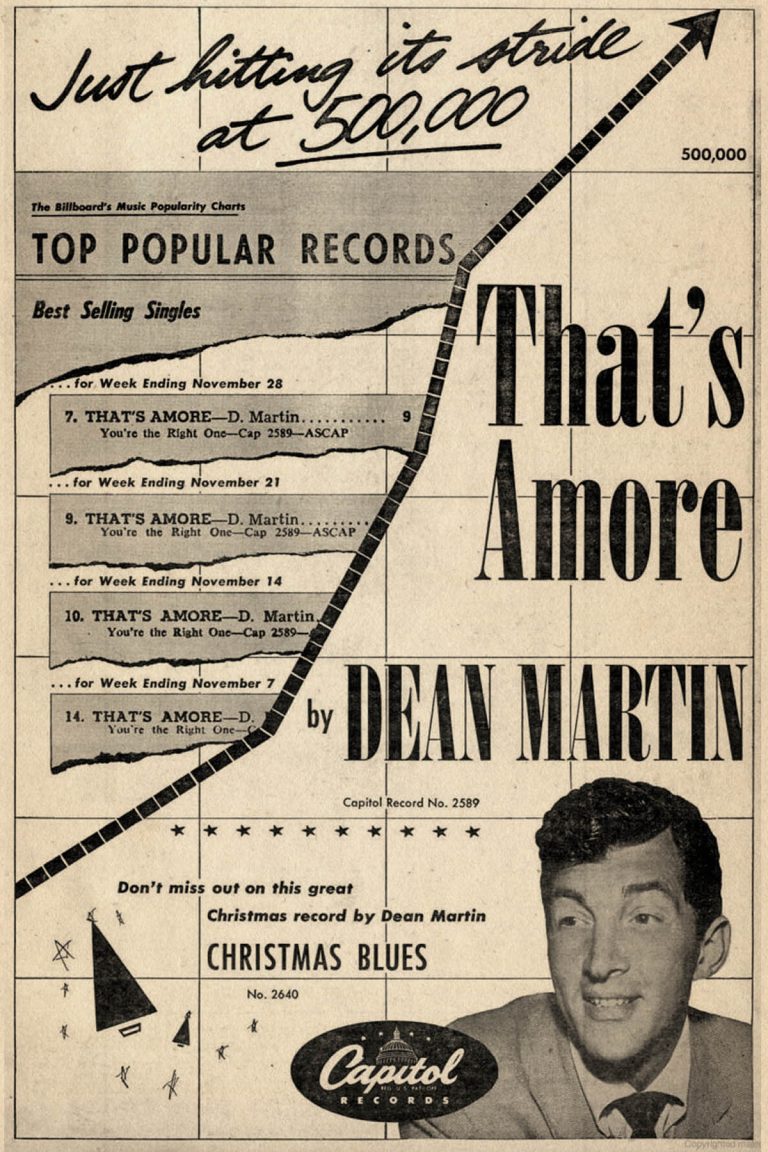

On November 25th, Dean sang it again for a national audience on the aptly titled Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis Present Their Radio and Television Party for Muscular Dystrophy. By December 12th, Billboard reported “That’s Amore” had sold half a million copies with an additional 150,000 more a week later. It peaked at #2 in both Billboard and Cashbox (unable to usurp Tony Bennett’s “Rags to Riches” nor “Oh My Papa” by Eddie Fisher from the summit) and Jerry had the honor of presenting Dean with a gold record on the January 10th 1954 broadcast of the Colgate Comedy Hour.

“That’s Amore” eventually sold over two million copies and was nominated for an Academy Award. Dean performed it at the March 25th gala ceremony, but the tune lost out to Doris Day’s “Secret Love” from the movie Calamity Jane.

There would be other “Signature Songs” to come for Dean Martin: “Memories are Made of This,” “Everybody Loves Somebody,” and “Ain’t That a Kick in the Head” all come to mind. But there was something about “That’s Amore” that was extra-special. In 1987, nearly thirty-five years after its initial success, it was heard over the opening credits of the motion picture Moonstruck which exposed it to a new generation.

And as a poignant close to one aspect of his long and successful career, Dean Martin sang live on television for the final time a few days before his 71st birthday in June 1988 on the Children’s Miracle Network Telethon. Fittingly, the final song he performed was “That’s Amore” – his first, and perhaps best remembered, “Signature Song.”

The “Plus Factors” of Stereo Cinematography by Hillary Hess

The general consensus is that none of the Martin & Lewis films captured the free-wheeling spontaneity of their live act as Jerry would cause comedic chaos while Dean crooned earnestly, appearing to maintain a glossy showbiz decorum. The closest the general public ever came to seeing that degree of improvisation from the team was on television programs like the Colgate Comedy hour in which they were largely given a free hand to do as they wish. This is understandable in the days of early television as the medium was finding its way and was voracious for programming, welcoming such lively and inventive acts. By contrast, the economics of motion picture production requires a greater degree of organization, and by necessity the team was inserted into more structured scenarios which may have blunted their comic invention, but by no means dimmed the effect of their personalities.

This brings us to MONEY FROM HOME in 3-D, its stylized Damon Runyon dialogue and milieu affording Dean and Jerry the opportunity to play it a bit loose with the characters. Throughout, Dean’s demeanor seems bemused, as if he’s having fun even when the life of his character, “Honey Talk,” is threatened. Jerry’s flexibility of body and face is in full force, and in the case of both performers, the 3 D makes this all the more palpable and entertaining. The chemistry between the two comes across in every scene they have together with the audience feeling this by the apparent proximity afforded by the stereoscopic medium.

Indeed, 3-D offers us some of that spark the team’s live audiences report, the energy produced when Dean and Jerry play off each other. And rather than divining this through vintage, barely standard definition kinescopes, we get to witness this in genuine Technicolor as if they are sharing our space, adding to the enjoyment. During live performances, Lewis was known to often break the fourth wall, running amok into the audience in comical frenzy. In MONEY FROM HOME, though a bit more staid than any of their live acts, the fourth wall does take an occasional hammering, beginning with Runyon’s only blandly-named character, “Sam” looking into the camera defending his lack of a nickname with “So sue me.” It makes sense for Jerry’s character, “Virgil,” to get opportunities to play with the z-axis as he runs into a busy street to save a dog from oncoming traffic, swinging from a hayloft rope, and most tangibly, walk directly toward the camera into the viewers’ space describing the “half nuts” nature of a Rudolph Valentino character.

That last scene sets up one of Jerry’s finest moments in the picture, and one which gives us a glimpse into his earliest showbiz days. The take on Cyrano de Bergerac in which Dean serenades Marjie Millar’s character “Phyllis” with Jerry lip-syncing to the music hearkens back to Lewis’ first foray into performing, which he referred to as his “record act” where he’d do just that; mime singing to various records. As Phyllis drowns out Honey’s “Talk” by changing the radio stations, the humor builds, culminating in some balletic buffoonery as Jerry’s Virgil attempts to follow the radio exercise program’s host, the distinctive voice of Jack Benny’s frequent foil, Frank Nelson , practically twisting himself into a pretzel. It’s wonderful to witness this bit, well integrated into the story, and surely responsible at least in part for Lewis’ screen credit for “special material and song numbers.”

On top of everything else, MONEY FROM HOME looks like a million bucks! With gorgeous Technicolor Stereo Dynoptic cinematography by Daniel Fapp, setting the scene with some positively transporting views of 1953 New York City, followed by an impressive (especially considering the weight and bulk of the Dynoptic rig) tracking shot along Paramount’s version of the city, proudly hyped in the trades by producer Hal Wallis. 73 years ago, Wallis assembled a team of skilled artisans to create a superb example of stereoscopic cinematography at its absolute zenith. Tragically only 2% of viewers got to see it in 3-D in theaters in 1954. Now, it receives its first ever wide and justified release in magnificent third dimension, providing us this unique opportunity to see Martin and Lewis in such a vivid medium once again delivering that energy for which they were rightly famous; this is a winner you can bet on!

Show Me the Money… From Home by Brandon Lang

As a recent inductee into the world of vintage stereoscopic film, I have been waiting with bated breath to view the new restoration of Money From Home. For the time I have known Bob Furmanek, this film has been looming over me like a specter. Finally, only a few days ago, I had a chance to experience the majesty of Hal Wallis’s 1953 stereoscopic motion picture. To say the least, it lived up to the hype.

Hal Wallis, while speaking about the future of 3-D in 1953, claimed that he does not, “regard 3-D as a passing fancy, nor do we believe that its interest relies on a so-called ‘gimmick’ value.” While watching Money From Home, I completely understand why he would say that. The picture features very little of the ‘gimmicks’ Wallis derides and instead employs 3-D as a way to enhance the experience and immersion into the story. The careful staging and meticulous compositions are done so to showcase the depth and advantages of stereoscopic photography. Wallis’s desire for verisimilitude here is reinforced by his later 3-D production, the film Cease Fire, filmed on location during the final days of the Korean War.

Having only recently graduated from film school, and as an ever-eager student of film history, learning more about the Golden Age of 3-D films has been a real treat. Finally getting to bear witness to Martin & Lewis and their classic antics all in glorious 3-strip Dynoptic 3-D Technicolor, the experience was well worth the wait. I would encourage any and all to give the film a shot and view it as it was intended: in glorious three dimensions!

Coming Soon!

Our painstaking restoration of MONEY FROM HOME – over two years in the making – is coming to Blu-ray this summer. Charlotte Barker and Andrea Kalas at Paramount Pictures’ Archive scanned 72 reels of Technicolor red/green/blue 35mm camera negatives totaling 54,000 feet of film. This complex restoration is truly the crown jewel in our catalog and 3DFA bonus features for this release will include the following:

Emmy and Murrow Award-winning documentarian Sean Thrunk has produced a new film with interviews from Chris Lewis, Leonard Maltin, Charlotte Barker, Greg Kintz, Jack Theakston, Dave Northrop, Mike Ballew, Bob Furmanek and more. Included in the documentary short is never-before-seen 16mm Kodachrome footage taken by Jerry Lewis while on location at the Northridge Farms stables in the San Fernando Valley.

Private recording by Dean Martin that was given to Jerry Lewis for his 27th birthday on March 16, 1953, compiled by Josh Carmona to photos of the surprise party on-set.

Photo collage by Brandon Lang with rare unseen photos taken during production.

Regular and Teaser theatrical trailers.

Commentary track from Jerry Lewis expert James L. Neibaur (co-author of The Jerry Lewis Films: An Analytical Filmography of the Innovative Comic) with a guest appearance by Mike Ballew, author of the upcoming definitive tome, Close Enough to Touch: 3-D Comes to Hollywood.

Watch for a pre-order link from Kino Lorber VERY SOON for this exciting Golden Age Blu-ray 3D release!