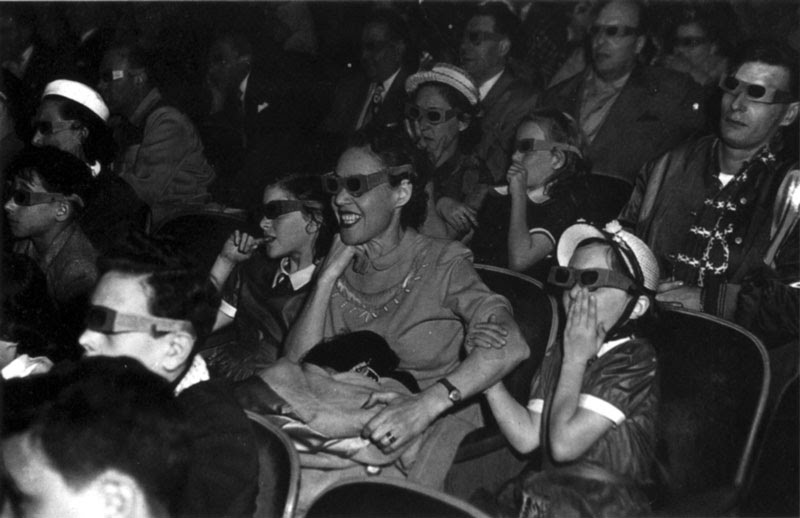

It is often written that it is the need to wear glasses that killed 3-D. But how did audiences in 1953 re ally feel about wearing glasses? As with anything, some history must be stated first to put things into the proper context.

When BWANA DEVIL premiered on November 26 1952, there had already been at least a dozen 3-D films shown in the US alone. The first feature was THE POWER OF LOVE, starring Noah Beery and Barbara Bedford, which was test screened on September 27, 1922 in Los Angeles at the Ambassador Hotel. There were examples of other 3-D test films shown to audiences before this film, but to all intents and purposes, THE POWER OF LOVE was the first time an audience saw a stereoscopic feature film.

After this, a slew of 3-D short subject novelties was produced, and even a feature, M.A.R.S. aka RADIO-MANIA. With the exception of M.A.R.S., all of these films utilized cardboard, anaglyph (red and green/cyan/or blue) spectacles that you held by hand up to your eyes.

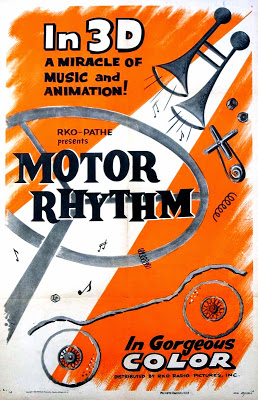

Dual-strip, Polaroid projection techniques became an enterprise in motion pictures on April 30, 1939 at the World’s Fair in Flushing, New York. John Norling’s animated short IN TUNE WITH TOMORROW was projected in black and white, dual-strip Polaroid 3-D. A year later, the film was remade in color as NEW DIMENSIONS, which was subsequently reintroduced to a new public in September 1953 by RKO-Pathe as MOTOR RHYTHM.

The viewers for IN TUNE WITH TOMORROW and NEW DIMENSIONS were cardboard spectacles that the audience member held with their hand to eye level (uniquely shaped like Chrysler Plymouths, the car that the short promoted), but unlike previous attempts, the lenses had magically become clear, not colored. It should be noted that this was not truly the first time that any audience saw Polarized 3-D– such an event had occurred at demonstrations given by Edwin H. Land, the inventor of Polaroid, in New York City during the winter of 1936.

But for IN TUNE WITH TOMORROW, Polaroid had made the breakthrough that was expected of them– instead of projecting just slides and crude home movies with their filters, it was time to go a step further and make the technology available for film makers who were interested in realism. After all– the cameras for shooting such things were already available and accessible. Men such as John Norling and Jacob Leventhal had been shooting footage in 3-D for years. The only limiting factors up until that point were the projection techniques– color filter-based anaglyph processes. Polaroid filters took things a step further by making the signals being sent from the film capable of being transmitted in color.

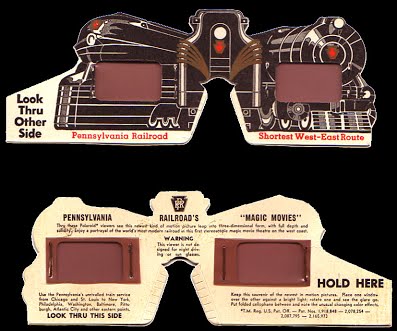

The following year, at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco, CA, the Pennsylvania Railroad Co. premiered their own travelogue in the Vacationland Building as “Magic Movies!” The eight-minute, black and white short entitled THRILLS FOR YOU came with a set of Art Deco glasses shaped like a train. For just a few moments, the audience got to see all of the luxuries of train travel as if they themselves were in the cabin with the wealthy folks that got to travel cross-country.

3-D sat dormant for another decade or so, with one or two items popping up as the typical “novelty.” World War II raged on, and Polaroid had far more important things to submit to the country than funny glasses and pictures that leaped off the screen.

Largely forgotten, it was in 1951 that 3-D was re-invented. During the Festival of Britain, numerous stereoscopic shorts were exhibited, many made by the Stereo Techniques company in the UK. In these instances, the spectacles took a new form thanks to the Polaroid Corporation, who had focused on comfortable glasses for stereo slide photograph projection. No longer did you need to hold glasses up to your eye– in the interim, Polaroid introduced the modern cardboard “flap glasses.” With tabs on the sides, the glasses rested comfortably over your ears, in the manner of normal glasses.

These were the glasses that were used when BWANA DEVIL first hit the screen. In a way, you could say that the film was the first American 3-D feature shot in color, or the first 3-D feature in the US shown in a Polaroid system. In any case, it was the film that started the public interest in the format. Because of BWANA’s groundbreaking technique, all of the features released in the US between 1952 and 1955 were shown with Polaroid glasses.

With the widespread release of 3-D films throughout the spring of 1953, more comfortable glasses were not the prime concern of those involved– quantity and availability was. Flimsy models put out by fly-by-night companies first flooded the market during the months following the November premiere of BWANA DEVIL. Polaroid warned exhibitors against such firms.

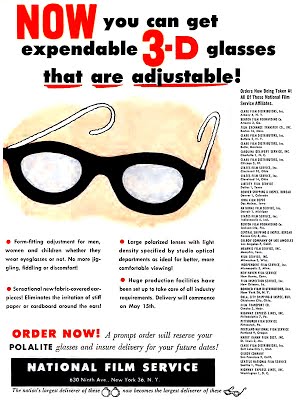

By May, a steady supply of quality 3-D glasses was being manufactured by a number of companies, including Polaroid. But the comfort of the glasses was still an issue that had to be solved. Polaroid and other companies worked feverishly on developing various models of glasses with varying degrees of comfort and adjustment.

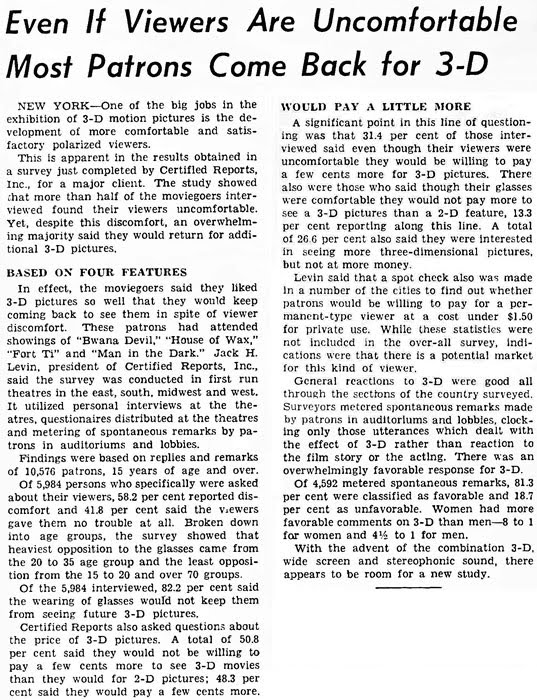

On July 25, a survey was published which began in February and lasted through a part of July. The study detailed the use of glasses in conjunction with stereoscopic pictures, and more importantly, what patrons thought of them.

While viewers felt the glasses needed to be improved, clearly it did not affect their choice to return to the movies for another dose of their favorite stars leaping off the screen into their laps. Film equipment companies were going at it all wrong with trying to fix the glasses. While they needed to be more comfortable, the glasses were clearly not the problem with 3-D films.

Time to Sync or Swim

It is often stated that glasses were the primary cause of headaches. This common misconception is repeated continuously by the press because the lay man does not know or understand the technical process behind stereoscopic projection techniques.

Projecting dual-strip 3-D is a science. I draw the line between an “art” and a “science” because for all practical purposes, a science is based on rigid fact and standard, whereas “art” utilizes talent and imagination. In order for a dual-strip 35mm presentation to work correctly, standards must be applied and adhered to at every performance.

In the dual-strip projection set-up, you have three key players: the projectors, the screen and the viewer. The first– projectors– must be of the standard change-over operational set. They must be able to handle 5000-foot, 23-inch reels rather than the normal 2000-foot reels. Both machines are being utilized and therefore cannot achieve a change-over without another set of machines in the booth. Therefore, all 3-D films must have an intermission. Both lamp houses must be balanced precisely, as both will be illuminating the screen at the same time.

Most importantly, the two projectors must be linked in a way that the electrical impulses of the motors to each projector are identical. This can be achieved in a number of ways, the most popular and most precise being that of Selsyn motors. Keeping perfect synchronization is of paramount importance. Every motion between the two machines must be identical– there is no margin for error.

If you’re running two films at once, and one film goes out of sync, even by a frame, your eye cannot adjust to the difference in motion. The result is a watery mess– it induces headaches and eye strain if not treated. Similarly, phasing of shutters has to be in perfect synchronization, too. Shutters must open and close at precisely the same moment. If one shutter is closed while the other is open, even at 1/8 of a frame’s difference, the viewer may not consciously note any issue, but the image will have issues similar to sync problems. The look on the screen is not particularly watery, but is more of a blurry, jerky look.

Framing is imperative. Two images can be easily aligned symmetrically by the naked eye, but it is important that the framing of the two images be perfect. Otherwise, the viewer’s eyes are straining to “lower” one image and “heighten” the other in order to converge the two. This also results in eye strain. This is the first item that should be checked before anything else, as it is the most noticeable and most painful.

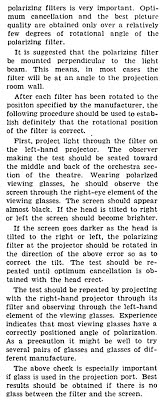

The two images are projected out through their respective ports through Polaroid filters placed over the port glass, which in turn filter what is essentially scattered light into vertical or horizontally polarized beams. When the beams hit the screen and reflect back, horizontal beams are picked up by their corresponding filters in the glasses and the vertical beams are reflected. This process works in a complementary fashion with the other filter.

The Polaroid filters have to be adjusted at precise right angles to one another in order to correctly filter out one another (in turn, these adjusted angles must be in conjunction to the glasses.) Turning a flat Polaroid filter at the wrong angle will change the direction of the light and therefore let unwanted light though to the complementary filter. This is why at many presentations of Polaroid 3-D, you cannot cock your head to an angle without compromising the 3-D image. The ghost image, or “crosstalk” as it is referred to, is your glasses picking up the perpendicular light beams.

Each Polaroid filter should be changed after several performances for optimum filtration. Polaroid filters are light sensitive, and after a certain amount of strong light is exposed to them, will lose their polarizing characteristics.

The screen to which these beams are projected must be metallic, preferably a silver screen. Because of its optical nature, metallic screens will reflect the two images without scattering the light beams, thus preserving the filtration effect.

A minor problem, fingerprints should be avoided at all costs on both glasses and booth filters. Fingerprints on Polaroid surfaces can compromise the 3-D effect.

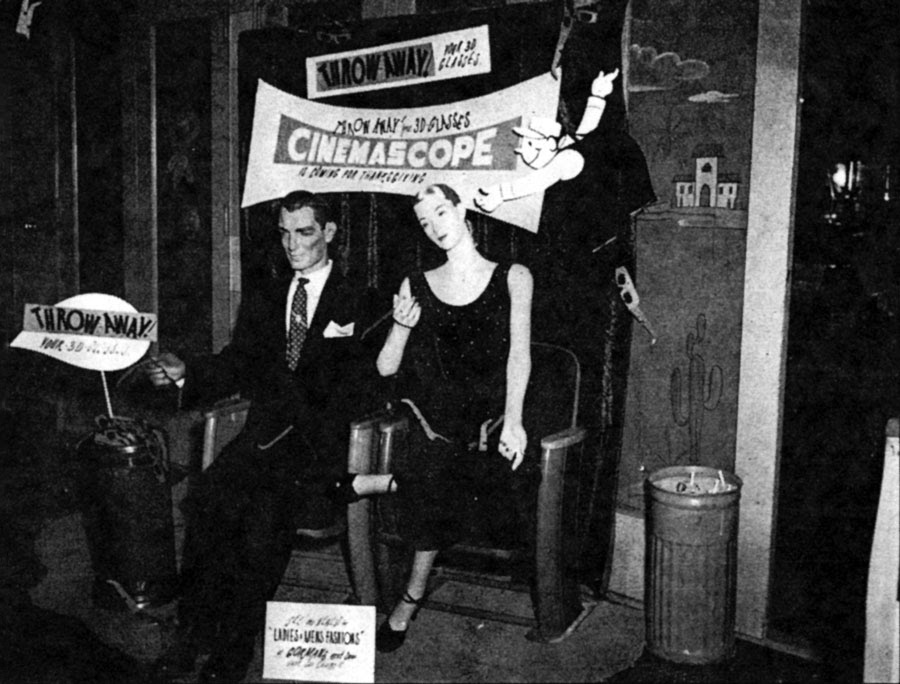

With all of these operational challenges, is it any wonder that exhibitors, projectionists and studios in the fall of 1953 embraced CinemaScope, the Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses?

Developments in technology always come at a stagnant pace. Had 3-D come as foolproof as CinemaScope had, perhaps we would be seeing half of our films today in a stereoscopic form. But unlike its predecessor Cinerama, 3-D had the disadvantage of confusion and imperfection working against it. Whereas Cinerama was a format far and few, its sparsity was its savior. Quality control ruled Cinerama’s grandeur, but 3-D unfortunately fell victim to many formats competing for the Exhibitor’s dollar, promising the same thing with different titles– Natural Vision, Paravision, Vitascope, Tru-Stereo, Dynoptic 3-D– it was all the same thing, but on paper, it seemed like a million different formats. When CinemaScope came to the Exhibitors’ door, the previous “gimmick” could be laughed off with profit.

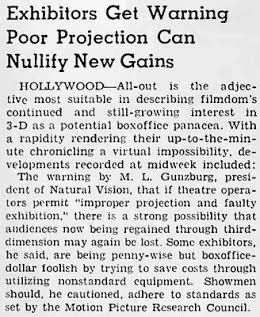

Thus, knowingly or not, there was a conspiracy to kill 3-D, and it was coming from all directions. It started with the projectionists. Sync issues kept creeping in. (As early as March 7, one month before the release of HOUSE OF WAX, M.L. Gunzburg had issued a statement on the need for a quality presentation.) From day one, even at press screenings and premieres, it seemed that projectionists had a tough time keeping sync.

Harrison’s Reports told of one such press event on April 11, 1953:

“In showing “Man in the Dark,” Columbia utilized 17-inch magazines, necessitating two intermissions. At the beginning of the second of the three parts in which the film was shown, the synchronization was so out of kilter that the showing had to be stopped for adjustment. Three separate attempts were made to bring the second part into synchronization but to no avail, with the result that, after a delay of approximately forty-five minutes, it was decided to skip the second part and to proceed with the third part. At the conclusion of the third part, the second part was screened, for by this time the trouble had been corrected.”

A couple of months later on June 13, Harrison’s Reports revisited the issue, citing the MAN IN THE DARK screening and another incident which took place just seven miles from the Warner Bros. studio in Burbank:

“But that was not so bad because the picture was shown, not to the public, but to the critics. Here is a case however that concerns the public, which paid good money to see a 3-D picture. It happened at the Wiltern, a Hollywood theatre owned by the Stanley-Warner circuit, during the showing of “House of Wax.” The two prints were out of synchronization by one frame for two days; the projectionist could not correct the trouble on the first day and continued showing the picture out of synchronism the second day. The result was that the eyes of the patrons were so strained that some of them suffered headaches while others became nauseated.”

What happened at the Wiltern wasn’t the only case of such an occurrence. According to Harrison’s, at the Criterion Theater in New York City during a showing of FORT TI, a show was canceled and more than one hundred admissions had to be refunded because the projectionist could not sync the two prints. That audience no doubt went home disappointed, but perhaps free, for the better, of a headache.

Many other trade screenings and premieres were shown poorly, including the important New York City world premiere of HOUSE OF WAX at the 3,664 seat Paramount Theater on Times Square. Billboard magazine reported, “The first day of 3-D pic, the projector broke down and caused a 45 minute lull.”

Even important films like KISS ME KATE, MONEY FROM HOME and DIAL M FOR MURDER had trade screenings that ran out of sync. The Martin and Lewis film is beautifully photographed in 3-strip Technicolor with the Dynoptic camera rig. The faulty preview caused Variety to state: “The 3-D process used for Daniel L. Fapp’s lensing got a poor display at the preview, the projection being off register often enough to cause considerable strain on the vision.” Hollywood Reporter added: “The 3-D is hard on the eyes.” As a result, most exhibitors booked it flat. When reviewing DIAL M FOR MURDER, Variety noted “Burks’ color photography is good, especially when seen flat as was the latter part of the picture at the preview when the 3-D went bad.”

Essentially, the sloppy presentations and inability to maintain synchronization is the reason why 3-D failed in the 1950s.

All of this trouble could have been easily remedied with more careful consideration of the prints. Built into most prints is edge coding– numbers that repeat in order every foot, so that the number of frames missing may be judged. Had the projectionists inspected the two prints side-by-side, utilizing the identical edge code printed in both “eyes,” they could have fixed the out of sync splice and gone on with trouble-free shows. Of course, that’s assuming the projection equipment was in perfect operation.

On top of the languidness of the projectionists personally, their union was asking for more money. At theaters running 3-D, the unions demanded that the Exhibitor employ an extra projectionist. And if you were running a film with stereophonic sound, forget paying two operators– you had to add a third one to thread up the magnetic sound print. Then, once the reel was going, said sound operator sat down reading the paper for an hour– on the theater’s payroll, of course. Because of the extra cost of the sound operator, the Paramount in Hollywood opted to play Columbia’s FORT TI in mono, rather than pay another wage.

As a result of all the faulty presentations, admission to 3-D movies began to decline in the last few summer months of 1953. On June 14, 3-D pioneer John A. Norling told the New York Times: “The technical mis-handling of 3-D motion pictures to date threatens the art with an early and untimely death.”

The 3-D boom had generated a tremendous profit for Polaroid. In the eight months since BWANA DEVIL had premiered, Polaroid viewer production had gone from 30,000 to 6,000,000 a week. They scrambled frantically to find a solution. What exhibitors needed was an invention that would remedy all of the problems that arose with a dual-strip projection system.

In July, Polaroid began working on a means to fix these issues and restore the public’s faith in 3-D movies. On October 5, at the Allied Industries convention and tradeshow in Boston, they introduced synchronization equipment that would solve the problems. An article in Boxoffice stated: “Polaroid representatives made a deep impression with their demonstration of an equipment kit that will simplify keeping 3-D films in synchronization. Nobody challenged the statement of the Polaroid people that their field studies showed more than 50 per cent of the theaters were showing out of sync pictures.” On October 8, a report was read and submitted to the SMPTE in New York by members of Polaroid’s research staff. Click here to read the full report.

On October 14, a Variety article stated: “What amounts almost to a last-ditch fight to keep 3-D alive is being made by equipment and specs manufactures with big financial stakes in stereopix.”

That same week, Paramount (and later Universal-International) dropped their requirement that 3-D films must play out their depth engagements before the films would be available in standard 2-D versions. Harrison’s Reports wrote on October 17: “Third-dimension pictures are no longer a novelty and are, in fact, doing mediocre business throughout the country. The exhibitors are having sad experiences with the current crop of 3-D films and, consequently, are beginning to avoid them like the plague. Matters have come to a point where many exhibitors feel that to advertise the fact that they are playing a 3-D picture is to invite the public to stay away from the box-office.”

Polaroid offered the synchronization kit to theaters free of charge for a two month trial period. It was then available to purchase for $95.00, which was below the actual cost. They placed ads in local newspapers assuring the public that new films such as HONDO and KISS ME KATE were better than anything they had seen before. They also sent seven engineers on a tour of 60 to 75 cities to lend technical assistance to exhibitors. In addition, comfortable plastic glasses and clip-ons were introduced to the public. The new equipment and glasses helped for a brief while and 3-D enjoyed a short-lived resurgence in popularity during the winter months of 1953/54.

The efforts to develop a viable-single strip projection system are detailed in The Bubble

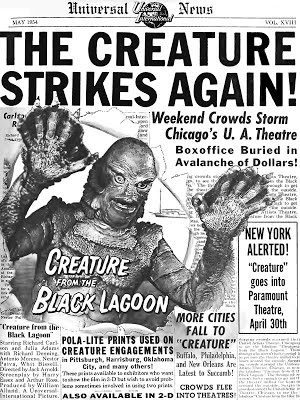

In February 1954, Pola-Lite offered a single-strip lens system (first demonstrated in June 1953) which would eliminate many of the problems found with dual-projector presentations. The left/right images were printed side by side on a single frame of film in an aspect ratio of 1.75:1. However, low light levels and reduced clarity (along with public apathy) worked against any potential for success of the system. Universal-International was the first to offer two films in Pola-Lite; CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON and TAZA, SON OF COCHISE. An ad in the May 28 issue of Film Daily mentions that Pola-Lite prints were also available for GORILLA AT LARGE, SOUTHWEST PASSAGE and GOG. However, there seemed to be little interest in Pola-Lite.

The studios had seen the writing on the wall. The final 3-D feature had gone into production in October, 1953. By the spring of 1954, the few remaining titles still on the shelf had limited bookings or were released flat. The final nail in 3-D’s coffin came on May 19 when audiences in Philadelphia shunned the opening day of DIAL M FOR MURDER. Warner Bros. had been the last holdout but with that development, all requirements for 3-D bookings were dropped. On May 26, Variety’s front page stated: 3-D LOOKS DEAD IN THE UNITED STATES. “Tri-dimension pix apparently have made their last stand in domestic distribution. There appears little interest among exhibs to show 3-D pictures.”

Universal-International released one last feature to theaters in March of 1955. Despite many 3-D bookings, REVENGE OF THE CREATURE effectively ended the Golden Age of 3-D.

In July 1954, 3-D pioneer John Norling wrote a scathing editorial for International Projectionist which you can read in the gallery on this page.